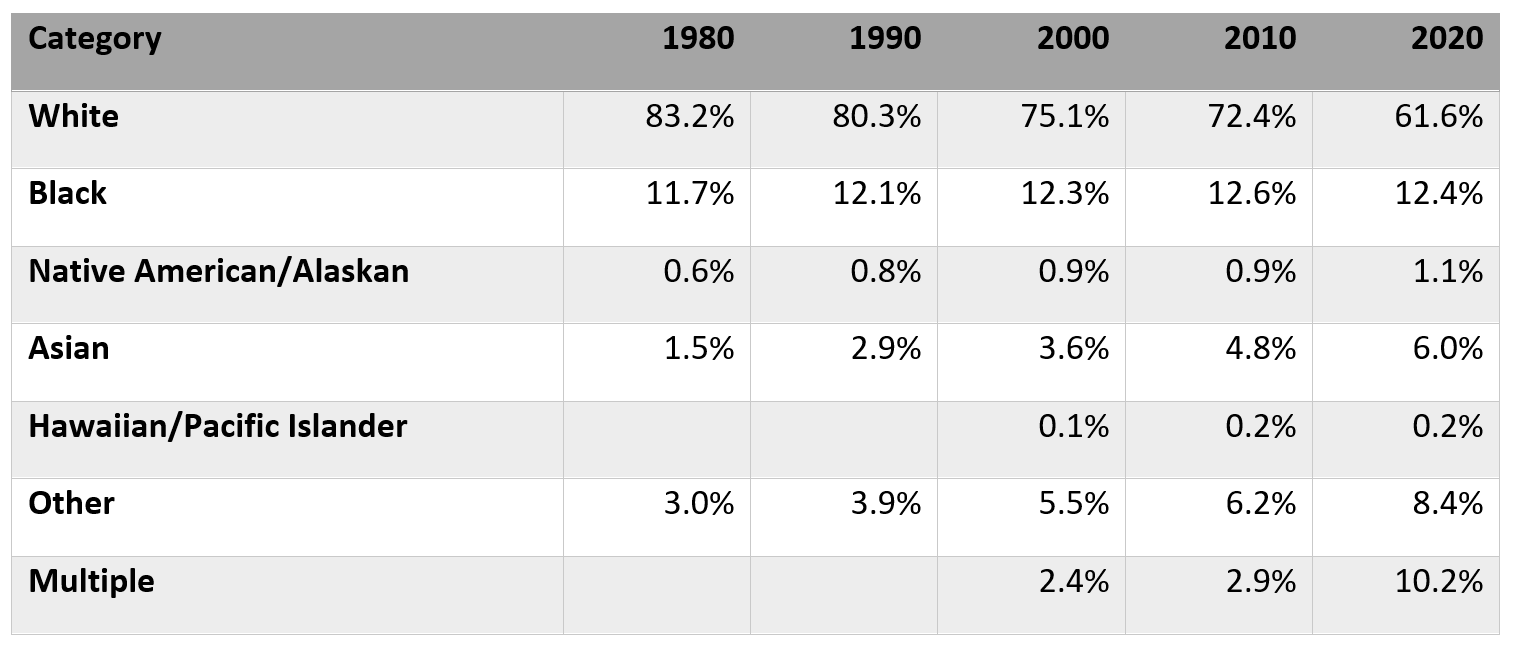

The recent publication of the redistricting release of the 2020 census has resulted in some discussion about some of its more surprising results. The white population declined from 223.5 to 204.7 million between 2010 and 2020, by all accounts an unprecedented change. The white population share of the total population has been declining over the last few decades, but this is the first decline in numbers:

A few things to note about the chart – prior to the 2000 census, respondents were required to select a single race, and those of Hawaiian/Pacific Islander were not separately enumerated. The way that the Census Bureau has quantified race has changed significantly over the years, and is well summarized in a census bureau graphic – Measuring Race and Ethnicity Across The Decades: 1790—2010 – U.S. Census Bureau – and thoroughly discussed in a working paper – Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United States.

Race as a classification of humans is at best a “squishy” concept, and one of dubious origins designed to justify slavery and colonialism in its early years (see race – The history of the idea of race | Britannica). While modern genetic analysis has been particularly hard on the classification, it remains in the forefront of public consciousness and so persists as a census measure. In one recent discussion, one of the conclusions was that “there is so much ambiguity between the races, and so much variation within them, that two people of European descent may be more genetically similar to an Asian person than they are to each other.” (How Science and Genetics are Reshaping the Race Debate of the 21st Century – Science in the News (harvard.edu))

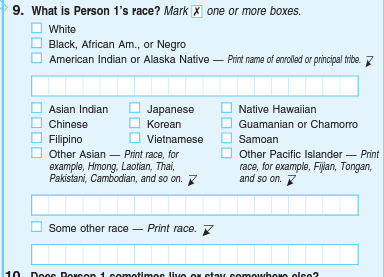

So, what accounts for the differences, especially between the 2010 and 2020 censuses? The Census Bureau claims that it was in the way that the question was asked. The 2010 census asked the question in the following format:

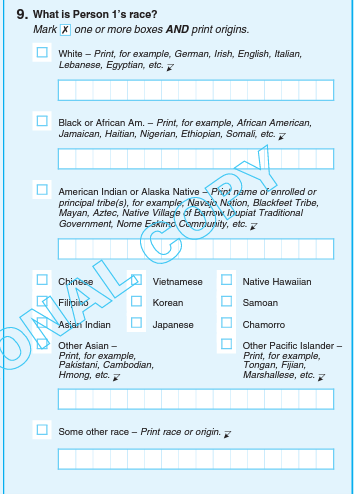

In the 2020 census, the question was asked as:

The differences are subtle, but highly significant. By asking people to identify their ancestry in addition to their race, it appears that many more respondents selected more than one box – hence the massive increase in the “multiple” race category. Likewise, if someone does not see their ancestry in the examples for each race, it may lead someone to choose the “other” category.

Aside from being an interesting study of how the formulation of a question, or group of questions, on a survey instrument affects the results, does this really matter from a practical standpoint? To the extent that consumers who identify as being of a different race behave differently (after controlling for other factors such as affluence and life stage), it does matter statistically to businesses who are targeting consumer segments.

Recent Comments