The practice of defining electoral districts by putting a finger or two on the scales is nothing new to American politics. In 1812, Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts was certainly not the first to draw electoral districts for the purpose of maximizing his party’s chances in the next election. The term ‘gerrymander’ rears its head at least once a decade, with one party shouting from the rooftops about the threat to democratic principles that will result from the adoption of the other’s proposed boundaries.

The Governor’s mistake was to draw a congressional district that looked remarkably like a salamander, and the press – specifically the Salem Gazette – quickly jumped on this and coined the term gerrymander (see https://www.si.edu/object/cartoon-gerry-mander-1813%3Anmah_509530). Sadly, the governor is known for little else, but at least he is famous for something.

The purpose of gerrymandering is almost always to gain an electoral advantage, and the constitution effectively ensures that the state governor gets to operate the scales. Districts can be designed to maximize the number of seats by two main methods –

- To distribute your vote across districts to win as many as possible without ‘wasting’ votes in those victories. A district won by 70% has 19% ‘wasted’ votes which could be deployed in adjacent districts.

- To concentrate the opponent’s votes into as few districts as possible, so that you maximize the number of votes that they waste.

The courts have generally sought to minimize the most blatant of gerrymandering schemes, especially those which have furthered their electoral goals along racial lines. Urban/rural lines are a different story, and many of the most interesting gerrymanders either cluster the votes of urban areas or dilute rural votes.

The current congressional districting includes a number of rather obvious gerrymanders – some in historically Democrat states, some in Republican states. In other words, it is an embedded part of our electoral system.

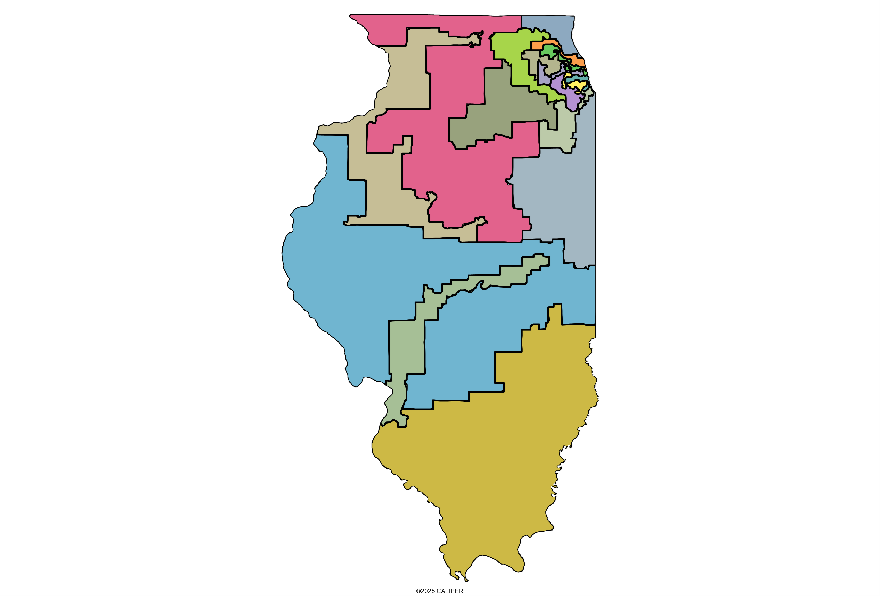

In Illinois, the districts outside of the Chicago area are less than compact:

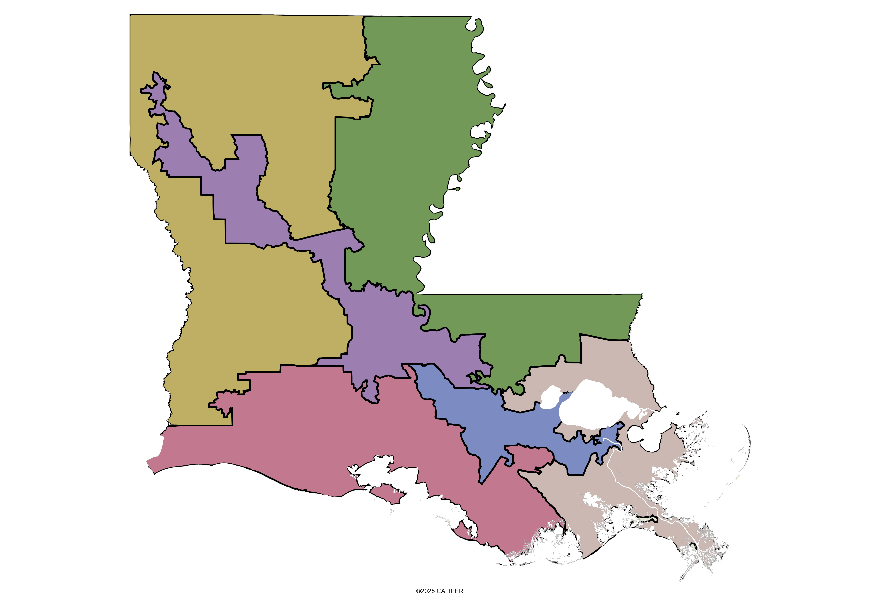

The purple district in Louisiana follows no reasonable boundaries, but manages to capture much of the urban areas of the state from Baton Rouge to Shreveport in one rather untidy district:

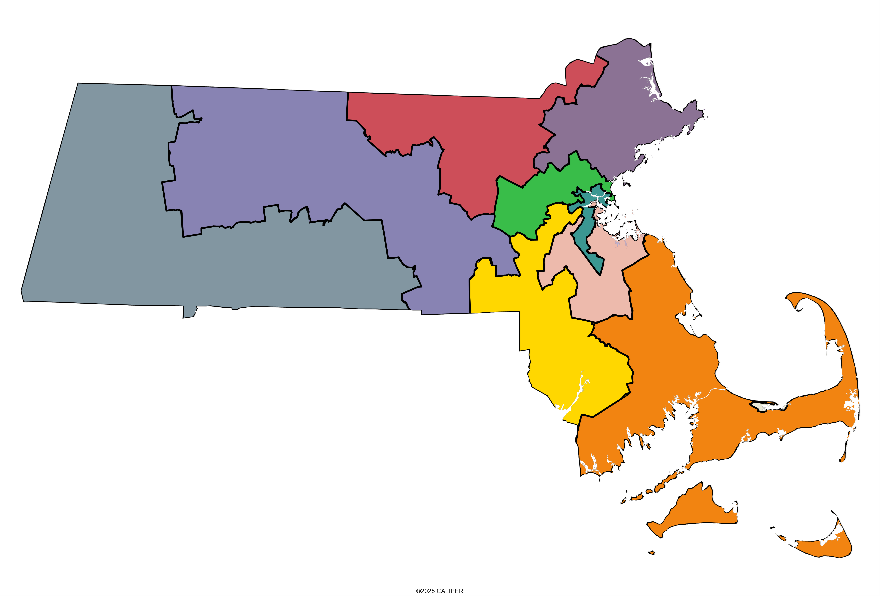

Likewise, in Massachusetts, the Boston area is split in a manner that Governor Gerry would most certainly approve, ensuring that the downtown core is paired with suburban areas:

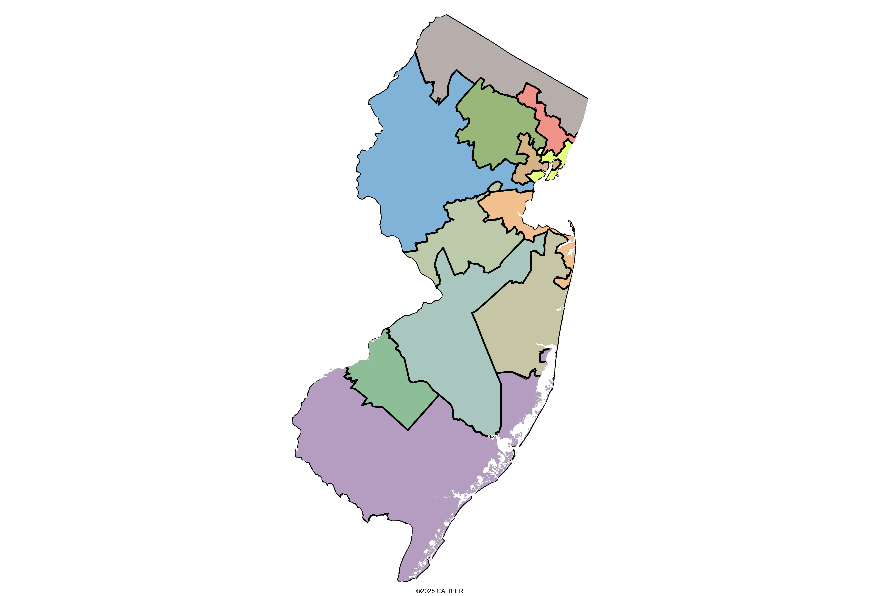

In New Jersey, a few of the districts consist of two or more distinct areas connected by narrow threads.

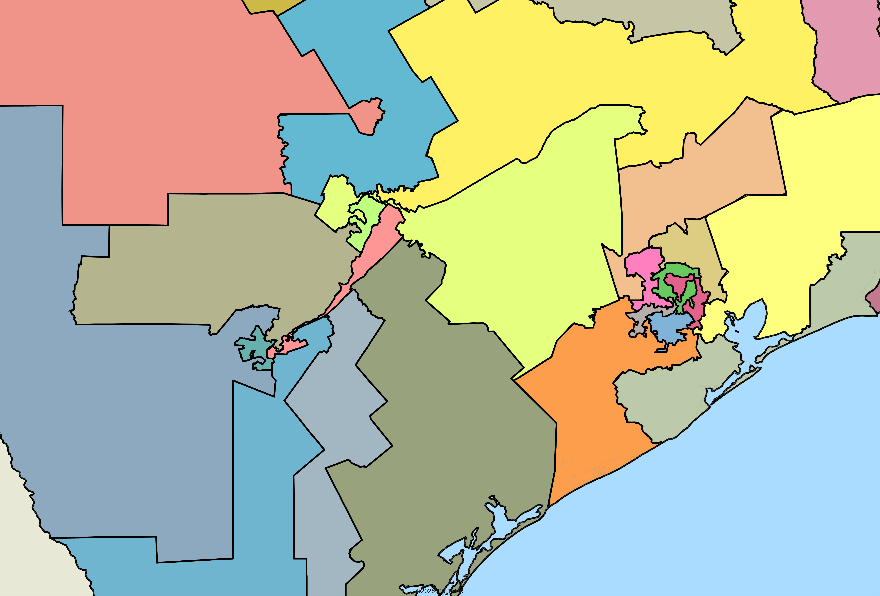

And finally, we note that the current boundaries in Texas include some spatial monstrosities in Houston, plus a particularly bizarre boundary that includes part of Austin and San Antonio, connected by the I-35 corridor and not much else:

Not that there would ever be agreement on these matters, but it seems to us that some basic rules could help here – roughly equal population with compact geographic areas should not be that much of a problem to define. There are spatial statistics which measure the compactness of any polygon, and there have been papers published over the years which have attempted to create equal and compact districts (for example, https://fryer.scholars.harvard.edu/publications/measuring-compactness-political-districting-plans). How does this problem get fixed? Reality is that it probably doesn’t. Decisions on how many seats a state gets are determined federally, while divvying up the state territory is done by within each state. It would take a constitutional amendment to modify this and enforce consistency between states, on which we doubt that there would ever be agreement. But it does provide a good political fireworks show, so grab some popcorn and sit back.

Recent Comments