We are often asked for a price adjusted income estimate, which sounds simple but is in fact extremely complex. There are, of course, many web sites which let you convert an income level in one city to its equivalent in another city – so if I live in Des Moines, Iowa, and have a household income of $100,000, what would be my relative income in Santa Barbara, California? After all, we know that gasoline on the west coast is much more expensive than in the Midwest, and certainly housing costs and taxes are substantially higher. The problem is that the scale of these estimates is generally based on metropolitan area or state level in non-metro areas. This tends to understate costs in more expensive parts of a city, and most definitely overstates costs in non-urban areas.

Of course, most users aren’t really interested in total income, but rather the income that a household has ‘left over’ after it pays taxes and buys the essentials of life. Economists have long used the terms disposable and discretionary income. For small geographic areas, these measures are often unavailable or are based on average and inaccurate estimates derived at larger geographic scales. Such measures are rarely helpful, since the scale within metropolitan area variation can be as great as between metropolitan area variation.

The AGS synthetic household model solves this issue by estimating total, disposable, and discretionary income at the household level then aggregating to the census block and beyond.

But first some definitions –

Disposable Income is defined as the total income net of income taxes (federal, state, or local). The AGS disposable income also includes social security contributions which are most certainly not voluntary. It excludes Medicare contributions, not because they are voluntary, but because they cannot be reasonably separated from Medicare premiums within the structure of the available consumer spending data.

Discretionary Income is defined as the amount of income that remains after the satisfaction of the basic human needs of shelter and food. Shelter and food are deemed to be ‘non-discretionary’, as are existing commitments to repay loans (cars, mortgages, etc.). The AGS definition of non-discretionary items is expanded and includes:

- Shelter costs (rent or mortgage plus property taxes)

- Homeowners insurance, since this is very often required by lenders

- Utilities including home heating fuels, water and sewage. Since it is not possible to determine what portion of electricity is for home heating, all electricity costs are included as non-discretionary

- Alimony and child support payments

- Food and non-alcoholic beverages purchased for consumption at home

- Health care insurance, including Medicare and related payments, since households are legally required to carry health insurance

- Certain transportation costs related to vehicle purchases and leasing costs, including insurance and registration

The remainder is deemed to be discretionary income, that is, the amount of income left over after basic living costs have been satisfied. The primary weakness of these estimates is that discretionary income is underestimated for low-income households because some subsidy programs (food stamps, rental subsidies, etc.) are not well documented and excluded from total income statistics – even within the Census Bureau surveys.

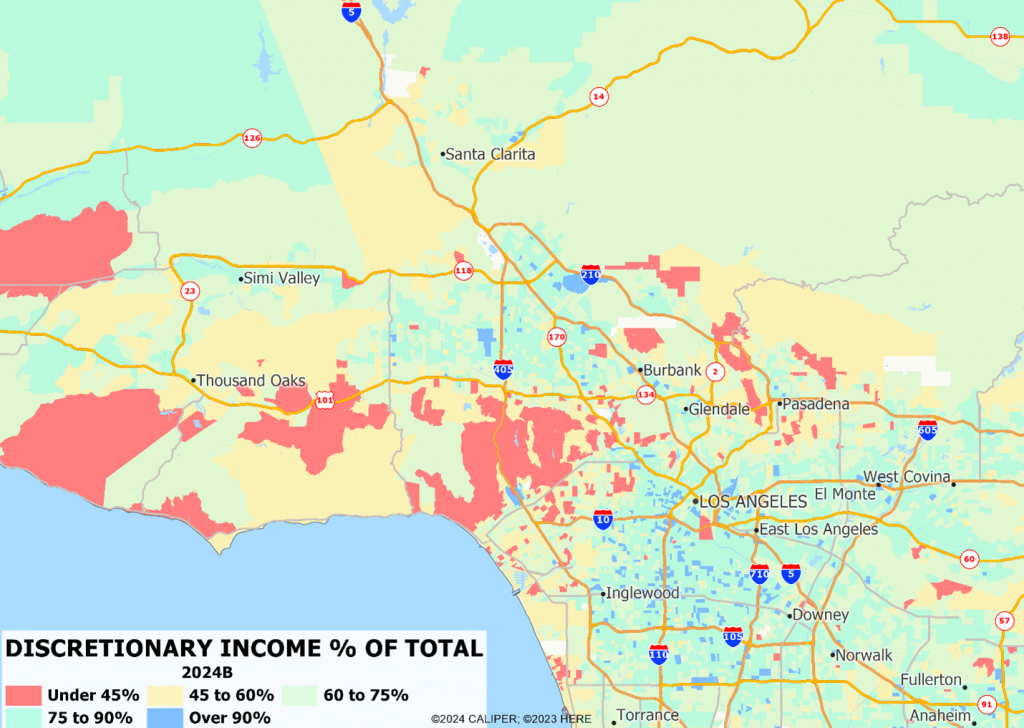

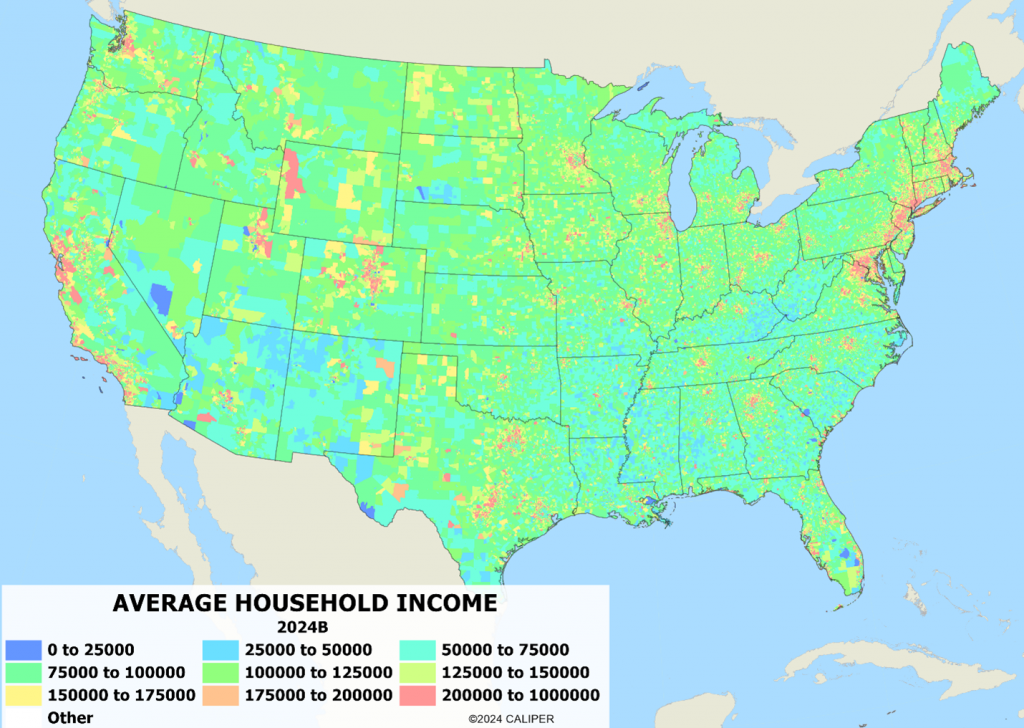

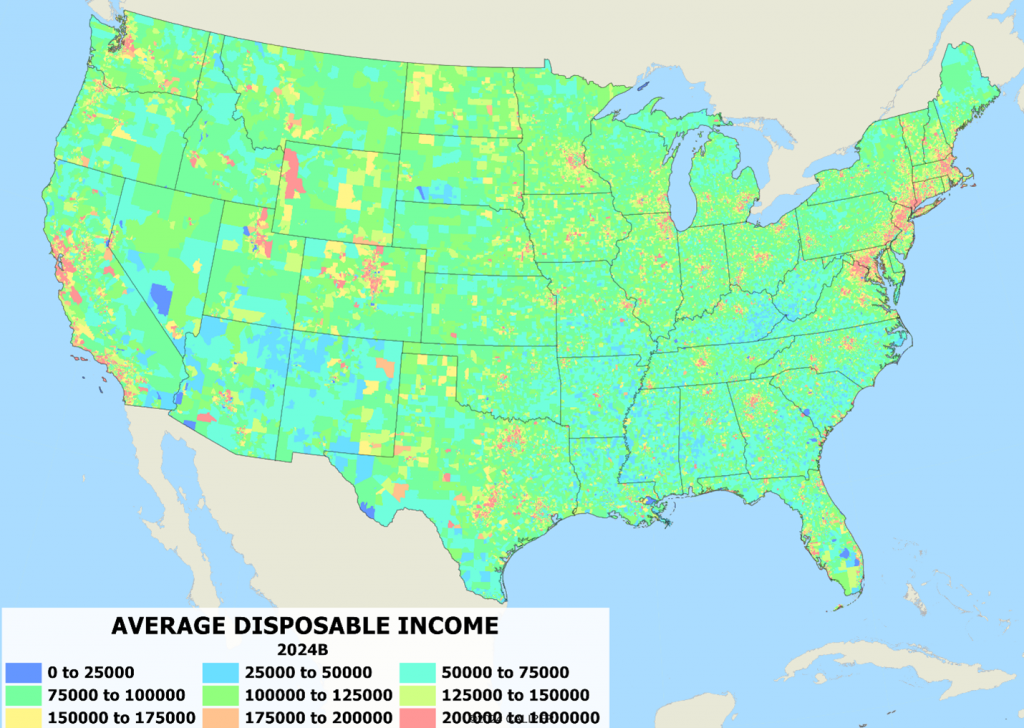

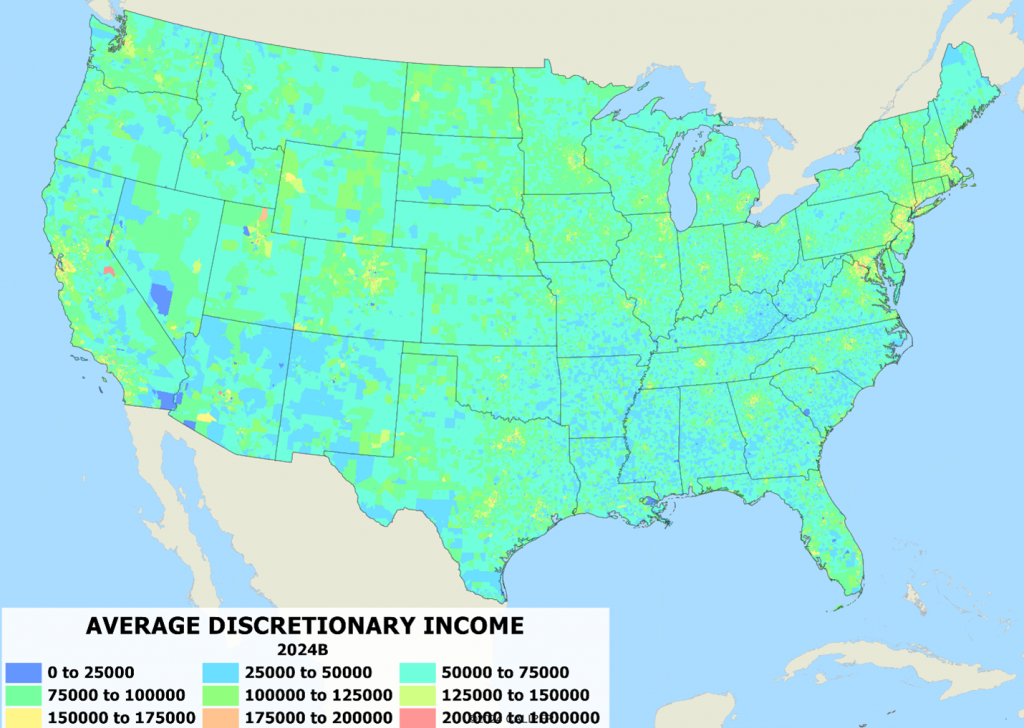

The maps below use the same scale for shading and show total income, disposable (after tax) and discretionary income: taxes and the cost of living are the great equalizers.

The results? We brought it close to home – Thousand Oaks, California, is an affluent outer suburb of Los Angeles, and for years we have wondered why there are so few decent fine dining restaurants. Based on income levels, there should certainly be more, but as it turns out, housing costs and taxation are so high that discretionary income levels are reduced substantially. The San Fernando Valley to the east has lower income, but taxes and essentials take much less of a bite and when combined with a larger market, the reason for the dearth of fine dining in Thousand Oaks becomes apparent: affluent, but with extremely high costs.