In 1992, when my family moved (temporarily, as we told our families) from Toronto to Los Angeles, one of our early discoveries was that upon hearing the words ‘out’ or ‘about’, many of our neighbors immediately claimed some level of Canadian heritage. This shouldn’t have surprised me, given that a significant share of my high school teachers were Americans, many of whom moved to Canada to avoid the draft. Also, my childhood best friend’s mom was from a town with a great name – Walla Walla, Washington. That she was American was of no consequence. And for many years, the border between Canada and the United States was simply a bridge to Niagara Falls, NY, where you slowed down so that some friendly guy in a booth could wave at you.

Ancestry is a vague concept at best. Growing up, I was told that I was a mix of German, Dutch, English, Scottish, a splash of French, and a dollop of Iroquois. Nobody ever said that my ancestry was ‘Canadian’, despite the unusual fact that both sides of my family were in Canada long before it became Canada.

My father’s family left Bavaria for the religious freedom of the Pennsylvania colony, and by the 1820’s the family was split between Pennsylvania, Texas, and what was then Upper Canada. Two hundred and fifty years after the family left Bavaria, my father was of German and Scottish ancestry, with the Iroquois dollop. The Dutch side of my mother’s family was among the early settlers of New Amsterdam, and when the British showed up in 1650, the land grant of Nassau County was shockingly nullified and the family, presumably with less than subtle British encouragement, headed north to settle New Brunswick. Nearly four hundred years later, my mother’s ancestry was Dutch and English.

In the latest ACS survey, a mere 5.5% of the population identify as having American ancestry. Compare this to Canada, where 16% declared ancestry as Canadian. A further 900,000 people declared ancestry as being French Canadian. Surprisingly, this is lower than the ACS estimated population of 1.6 million French-Canadian ancestry in the United States.

There have been significant migrations in both directions over the years –

- The British expelled most of the Acadians of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island between 1755 and 1764, and those who ended up in Louisiana became known as Cajuns. Nearly 100,000 identify as being of Cajun ancestry.

- After the revolutionary war, 3-4% of the American population fled for the remaining British colonies which would become Canada.

- In the early 1970’s, estimates run as high as 100,000 Americans left for Canada to avoid the Vietnam era military draft.

- Substantial numbers of Canadians, especially from Quebec, moved to New England and the Great Lakes states pursuing economic opportunities in the rapidly industrializing United States

All this to ask the question – how many Americans live in Canada? And how many Canadians live in the United States? The answer is that we really don’t know, and the ancestry data in each country, while useful, is most certainly understated. The patterns, however, are likely consistent:

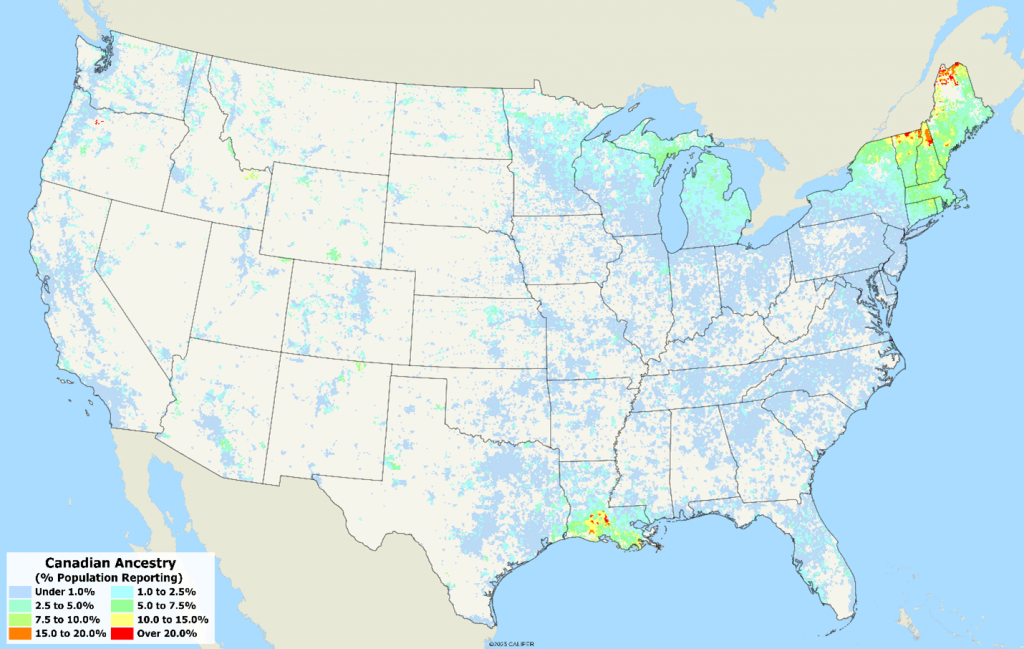

Canadians in the US are highly concentrated in New England, Michigan, and south Louisiana —

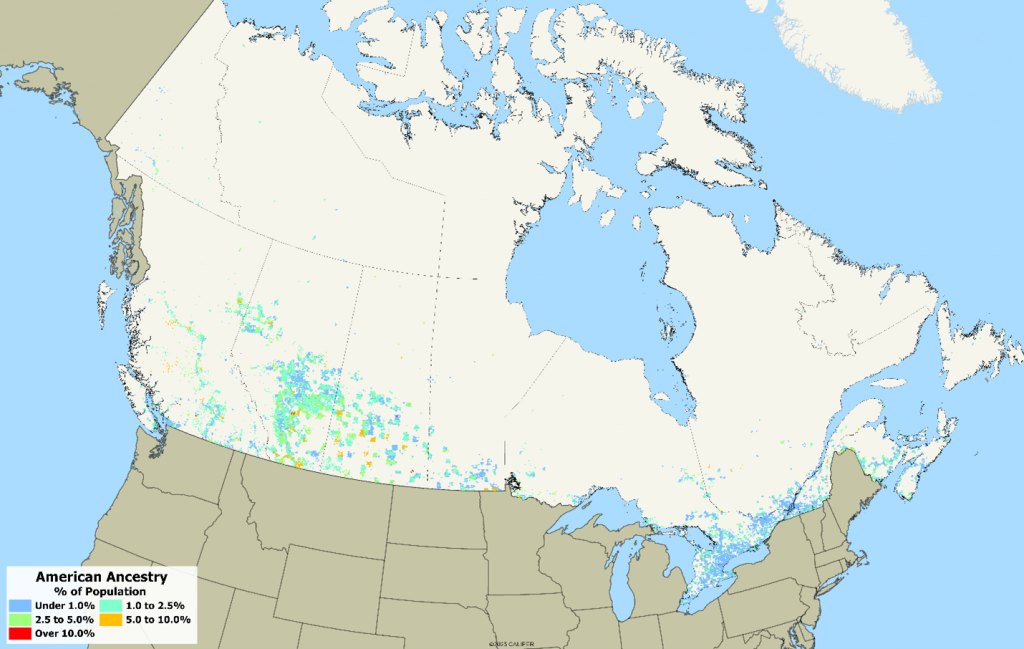

On the other hand, Americans in Canada tend to be in Southern Ontario or in the mining towns and oil fields of Alberta and British Columbia —

What does this all mean? Ancestry can be useful to the extent that there are cultural or behavioral differences between people groups. In most cases, this reflects the dominant period of immigration for any group – the more recent, the more relevant the ancestry response.

Ancestry is likely the least accurate for people in either country who are of European origins, regardless of how long they have been Canadian or American. The only real exception to this is the identification of French Canadian in the US, but we suspect that this is interesting information, but not likely useful. If you are using ancestry data for interest purposes, great, but be aware of the limitations of self-identification.

Recent Comments