The population of Canada has for decades growth at a relatively stable pace of about 1% per year. From 1971 to 2021, the population increased from 21.6 to 36.9 million people, averaging around 1% growth per year. Since the 2021 census, however, the population has grown by 12.3% in just four years, with nearly 4.5 million people added. This growth is largely because of radically increased net immigration, not through natural increase.

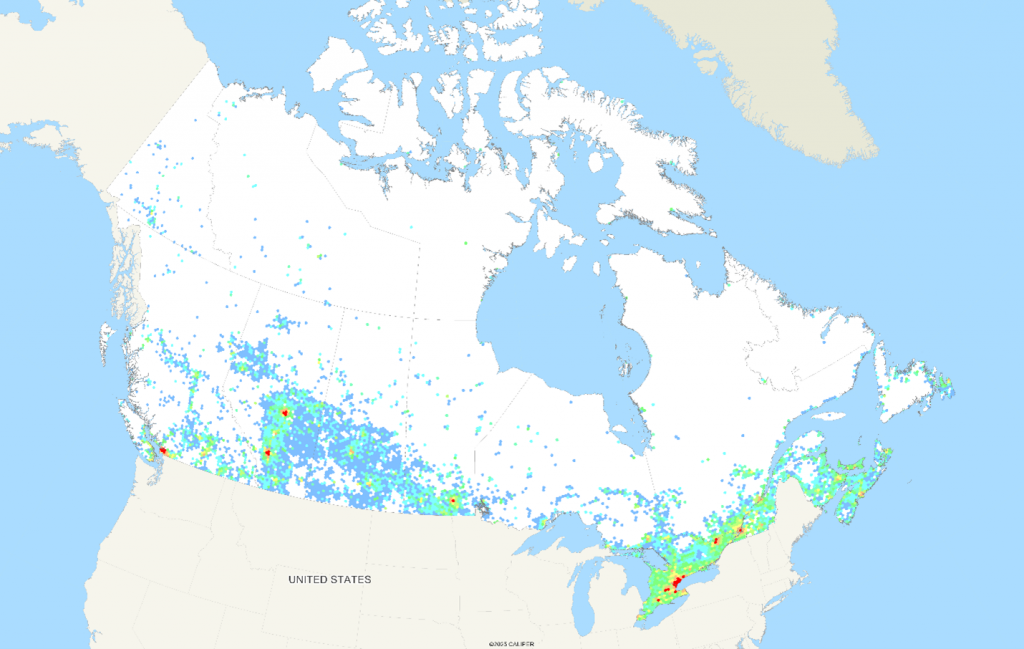

The map below, drawn using level 5 hexagons, shows populated areas with significant growth over the past four years:

Of the 293 census divisions (roughly county equivalent), only six declined in population, and areas of the country which have seen little population growth in decades are increasing in population.

Despite this, most of the population growth from 1971 to today is centered in just a few areas:

- Southwestern Ontario (Windsor to Oshawa)

- Toronto grew by 915,000 people to 7.1 million

- Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo increased by 21%

- London grew by 15.5%

- British Columbia’s Lower Mainland (Vancouver)

- Vancouver added nearly half a million people, growing by 18%

- The Alberta Corridor (Calgary to Edmonton)

- Calgary displaced Ottawa-Gatineau as the country’s 4th largest metropolitan area with a 21% increase in population

- Edmonton followed with 17%

Meanwhile, the major metropolitan areas of Quebec, while growing, grew much more slowly than cities in neighboring Ontario. Indeed, growth in largely French speaking areas of the country were slower growing than elsewhere.

Why the difference? The reasons are twofold –

- much of the immigration in recent years is from countries like India and Pakistan, and many in those nations speak English as a second language.

- most of the economic growth in Canada in recent decades has been in southern Ontario and the western provinces, and much of eastern Canada (especially Francophone areas) have not kept pace.

As a result, cities like Montreal, Quebec, Sherbrooke and Trois Rivieres have not shared in population growth to the same extent as other cities. Few immigrants have settled in Quebec outside these larger cities, and that is not the case elsewhere. For example, many smaller towns in Saskatchewan have seen considerable growth in recent years despite decades of decline.

One of the main effects of this rapid growth has been felt in the housing sector. The rapid influx of new residents, especially in Toronto and Vancouver, has resulted in rapidly rising housing costs and decreased rates of home ownership. Toronto and Vancouver often appear on lists of the world’s most expensive cities to live in.

In Toronto, the city itself grew from 2.8 to 3.3 million people in just 4 years. The only way to increase the housing stock is to redevelop existing areas, since very little undeveloped land remains within the city limits. Rapid increase in demand with little increase in supply means exploding prices. Building housing takes time under the best of circumstances, but add in excessive government regulation and fees, and you have a full-blown crisis on your hands. Long-time residents increasingly find it difficult to resist selling their properties at great gain and purchasing houses miles from the city – driving up prices in small towns like Collingwood and Wasaga Beach.

The surge in net immigration and the housing affordability (and availability) crisis in many Canadian cities are of course highly related. Increasing pressure on government to “do something” about the housing problem will likely result in a slowed pace of net immigration over the next few years, although most certainly other solutions will be first attempted. Indeed, population change from 2024 to 2025 is at the lowest level in recent years, but it will take several years to balance the supply to demand.

Recent Comments