Floods are among the most destructive and misunderstood natural hazards in the United States. While hurricanes and tornadoes dominate headlines, flash floods quietly take more lives on average each year. According to NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory, flash floods—which occur within six hours of intense rainfall—kill more people annually than lightning, hurricanes, or tornadoes. And no part of the U.S. is immune; flooding occurs in all 50 states and every U.S. territory.

Flash floods can stem from a wide range of conditions, and they often arrive with little warning. Common triggers include:

- Heavy rainfall after drought – Dry, compacted soil can’t absorb water quickly, causing rapid runoff.

- Spring snowmelt – A sudden warm-up can release massive amounts of water across vast river basins.

- Hurricane storm surge – Coastal and inland flooding alike can be devastating.

- Dam or levee failure – Man-made barriers can fail catastrophically.

- Urbanization – Concrete and asphalt speed up runoff, often overwhelming stormwater systems.

Often, it’s a combination of these factors that create the most damaging events. While devastating in the short term, flooding has also played a critical role in shaping some of the world’s most fertile agricultural lands—from the Nile Delta and China’s river valleys to California’s Central Valley and the ancient floodplains of Mesopotamia.

Historical flood events underscore just how wide-ranging and destructive flooding can be:

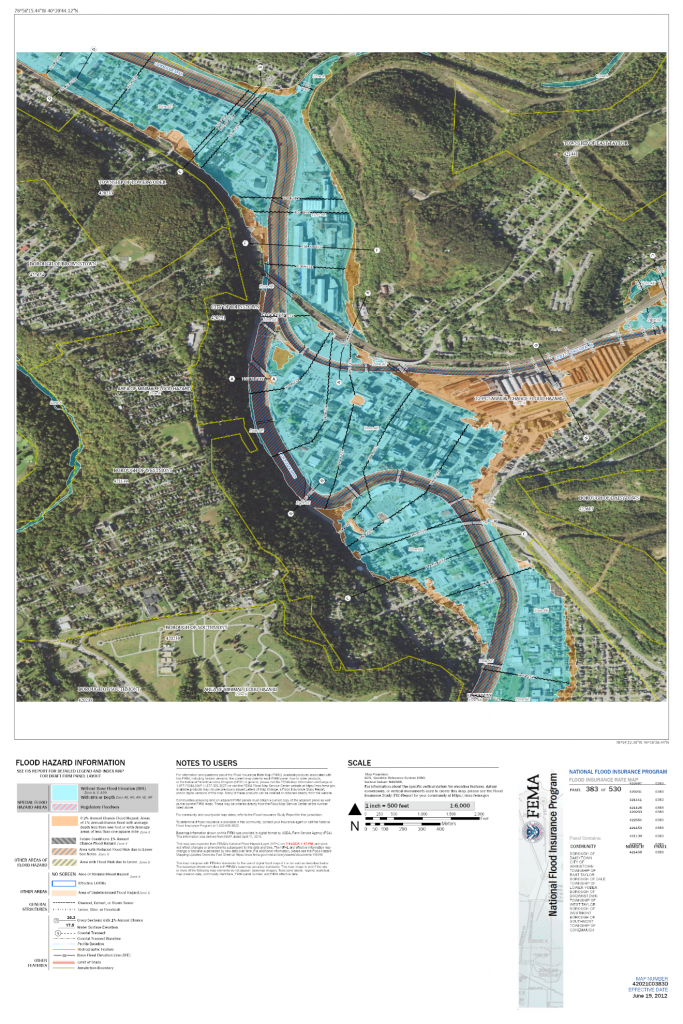

- Johnstown, PA (1889): Days of heavy rain and the collapse of the South Fork Dam led to over 2,200 deaths in one of America’s deadliest floods. Maps of current flood risk areas in Johnstown, like those available through FEMA’s Map Service Center, still show the vulnerability of the region.

- Great Flood of 1862: Spanning from British Columbia to Baja California, this 43-day deluge transformed California’s Central Valley into an inland sea. Sacramento was under 10 feet of water. Some regions remained flooded for over a year, and more than 1% of California’s population perished.

- Great Mississippi Flood (1927): One of the most devastating U.S. floods ever, it displaced over 700,000 people and inundated much of the lower Mississippi River Valley.

These events are stark reminders that extreme flooding is neither rare nor bound by geography.

FEMA’s terminology, like “100-year flood,” often causes confusion. It doesn’t mean that such a flood happens only once in a century, it means there’s a 1% chance of such a flood occurring in any given year. These probabilities are independent each year, so having a flood in one year doesn’t lower the chances of it happening again soon.

This misunderstanding can lead to under-preparation and misplaced confidence. It’s similar to how weather forecasts transitioned from categorical (“chance of rain”) to probabilistic models—more accurate, but easier to misinterpret. When FEMA labels a property in a 100- or 500-year floodplain, it’s about risk exposure, not prediction.

The problem isn’t just one big flood—it’s the cumulative toll of frequent, localized events. More than 250,000 properties in the U.S. have made multiple claims through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), yet less than half of all homeowners in FEMA-designated flood zones carry flood insurance. Flooded Again: Visualizing Repeated Flooding Across the U.S.

This disconnect leaves many vulnerable—not just financially, but also physically—when the next event inevitably strikes. And as urban development increases impermeable surface areas, the risk of flash flooding only grows.

The good news? We have powerful tools to understand and mitigate flood risk. FEMA flood maps—like the one shown below—offer critical insight into flood-prone zones, base flood elevations, and areas protected by levees or floodwalls. They are essential for:

- Developers assessing site viability

- Municipalities planning infrastructure

- Homeowners evaluating risk and insurance needs

- Emergency managers preparing evacuation and response strategies

Recent Comments