Toronto has long been hailed as a great example of a public transit system that works. For many years, the downtown core was where all the job action was – the banking and insurance towers, the countless government buildings known as Queen’s Park, the University of Toronto, and the city’s major hospitals were concentrated into the compact area bounded by Bloor Street, Lake Ontario, Spadina Avenue, and Jarvis Street.

The bus, streetcar, and subway system were all directed at the downtown loop, making public transit the preferred means of traveling to work from most of the city. Once downtown, you did not need to brave the cold and snow outside, as an extensive underground pedestrian network links most of the major downtown destinations, albeit with near non-existent signage. For commuters coming in from further afield, the GO-Transit commuter trains operated in multiple directions from downtown Union Station.

Further, unlike many North American cities, the freeway network was an early victim to the anti-freeway movement of the late 1960’s and 1970’s, which made getting downtown from some parts of the city rather unattractive. A series of radial freeways headed to the downtown core became just two, with one freeway cancelled mid-construction.

Even as kids, we thought nothing of catching the Lawrence 54B bus from the blue collar neighborhood in the east end of Scarborough that dropped us at the end of the Bloor-Danforth subway line. Downtown was no more than forty-five minutes if you timed the bus right – which wasn’t hard given that the bus was every ten minutes, even from the edge of the city. In short, the transit system was widely hailed as one of the best and most efficient in North America.

The TTC, despite its success, requires significant subsidies from the city of Toronto, the province of Ontario, and the federal government in order to survive. Even the best public transit systems cannot operate without subsidy – and in the case of the TTC, nearly 2/3 of the current operating budget comes from government not from riders.

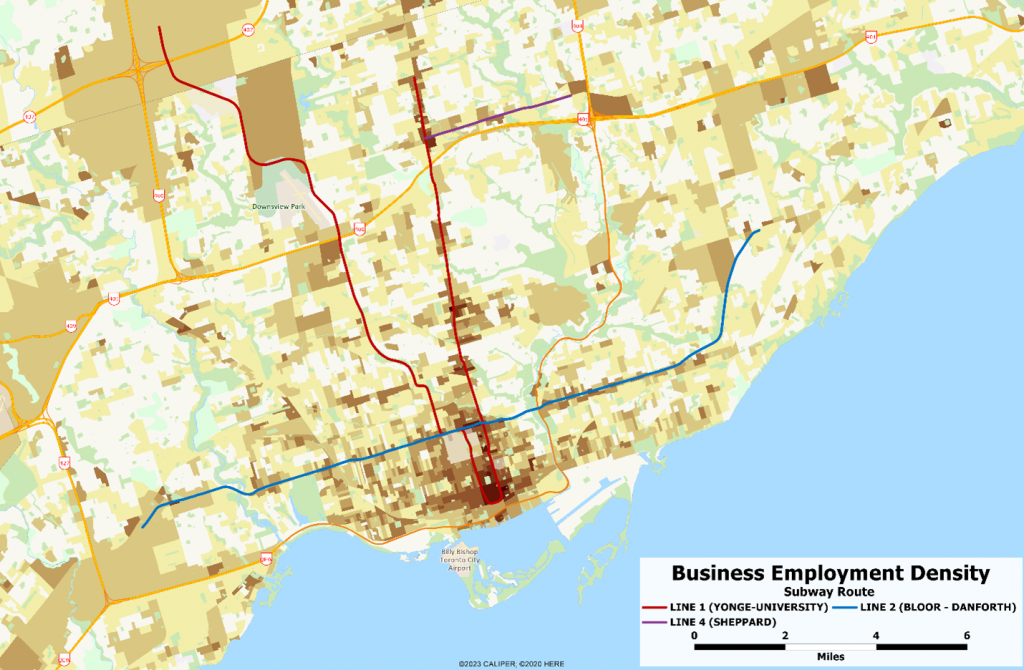

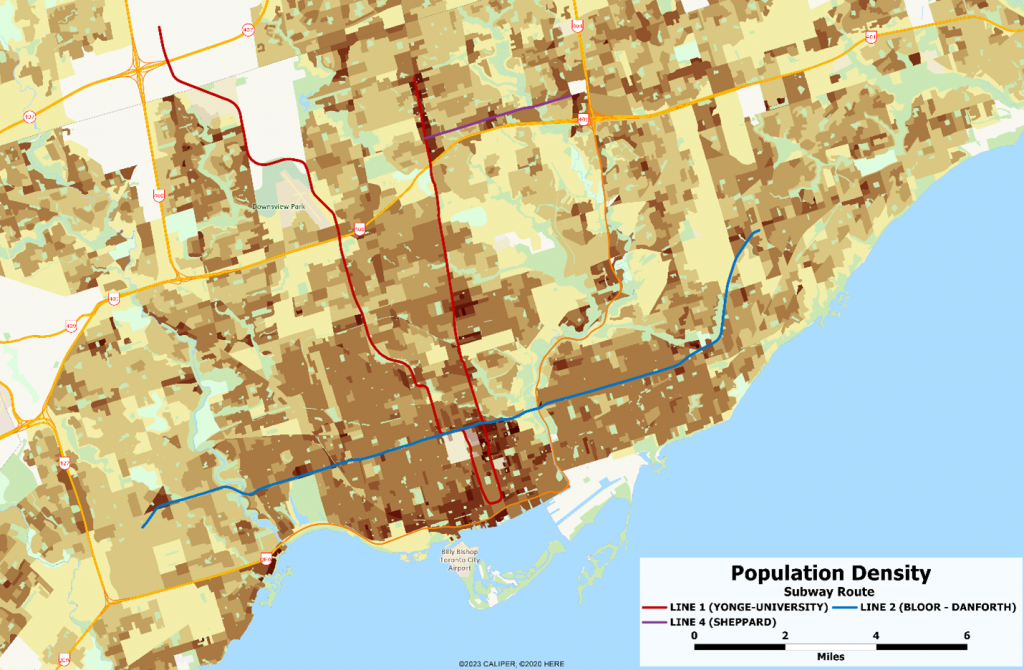

What of that city remains some fifty years later? We mapped population density and business employment density for the city of Toronto, showing the current subway lines:

Employment is still highly concentrated in the downtown core, with significant clusters of employment all along the Bloor-Danforth (east-west) line, and along the Yonge-University-Spadina line which loops downtown from the north and northwest. Additional clusters can be easily seen along most of the original streetcar routes, and in fact the TTC plans subways along several of those routes.

Over the years, major employment clusters have formed along the major suburban freeways which ring the older part of the city. These freeways have resulted in employment clusters, and have allowed the city to spread well beyond its 1970’s extent. Those living in the city are most likely to still take public transit to the downtown core, but the suburban jobs allow people to drive in from further afield.

Toronto, unlike many cities in North America, has not only retained its high density residential downtown, but in some ways expanded it. In recent years, the lakefront has been converted from warehouses and freeways to luxury condominiums and apartment buildings that extend from downtown west to the Humber River. The east end, known as the Beaches, was always residential.

But note the high population densities along the subway lines, especially on the Yonge north-south line, where apartment buildings cluster around the stops.

The spatial patterns which define a city like Toronto have been decades in the making and are largely determined by topography and transportation. The investment in new subways within the city should pay off long term by helping to keep the downtown core as the city focal point.

Recent Comments