The first of two inflationary periods of the 1970’s began early in the decade and was particularly hard felt in the hot real estate markets of urban California. Property taxes were completely tied to the annual market valuation conducted by the county assessor. During the initial inflationary period, people rushed to buy into the housing market before it became unaffordable and drove prices through the roof. The rapid population growth at the time put enormous pressure on local governments to provide ever more expensive infrastructure and schools. Many had their property taxes doubled or tripled over just a few short years.

That tax bill was the flash point for a taxpayer revolt which was led by Howard Jarvis. The state constitution allows for non-legislature sponsored ballot measures if enough eligible voters sign a petition. And sign it they did, and the proposition, given the number 13, appeared on the ballot in November 1978. Among other things, it amended the state constitution by limiting changes in property taxes to a maximum of 2% per year, based not on the current market assessment but on the price the owner paid for it the real estate asset. The proposition was passed by a two to one margin and embedded in the state constitution.

What does it look like some 45 years later? The AGS national parcel file, to be released at the end of summer, provides some significant insights. We chose a few development tracts in Thousand Oaks and looked at the range of property taxes paid, and the taxes per square foot of dwelling.

Take two houses, roughly the same size and market value. One pays $2,500 per year in property taxes, the other $10,000. Why? One bought their house in 1990, the other in 2020. Their use of municipal and local services is roughly equivalent, yet one pays four times the other in taxes.

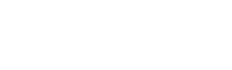

The property taxes paid vary significantly even along single streets. The map below shows the Wildwood tract of Thousand Oaks, built in the 1970’s – with some residents paying under $2,000 a year in taxes, and some paying over $14,000 – often for the same size and model house.

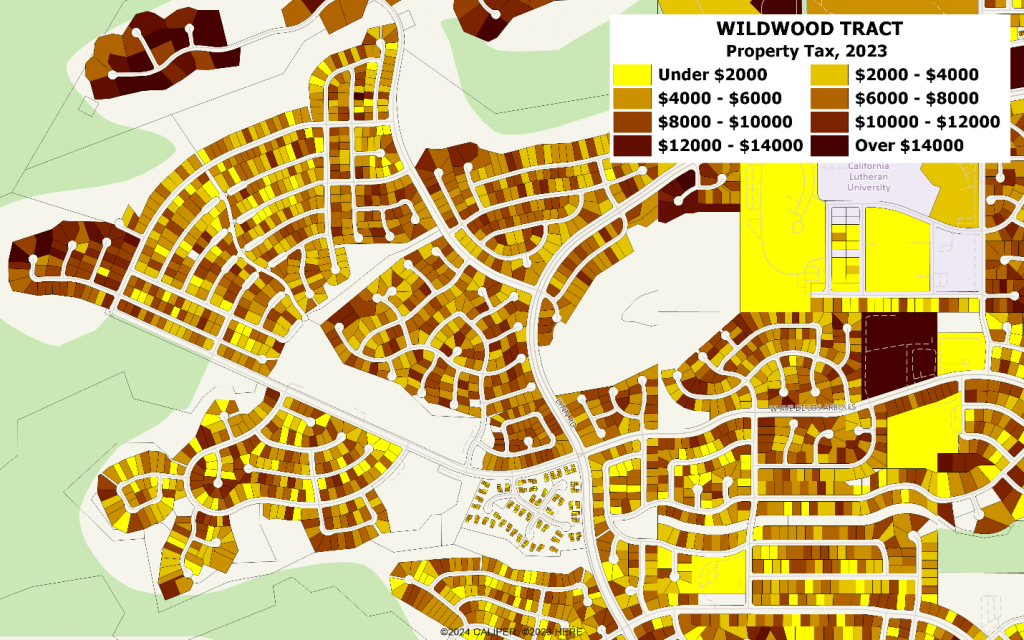

When we standardize by the size of the house, in square feet, we can see that there are substantial differences not related to the size of the house or the property acreage:

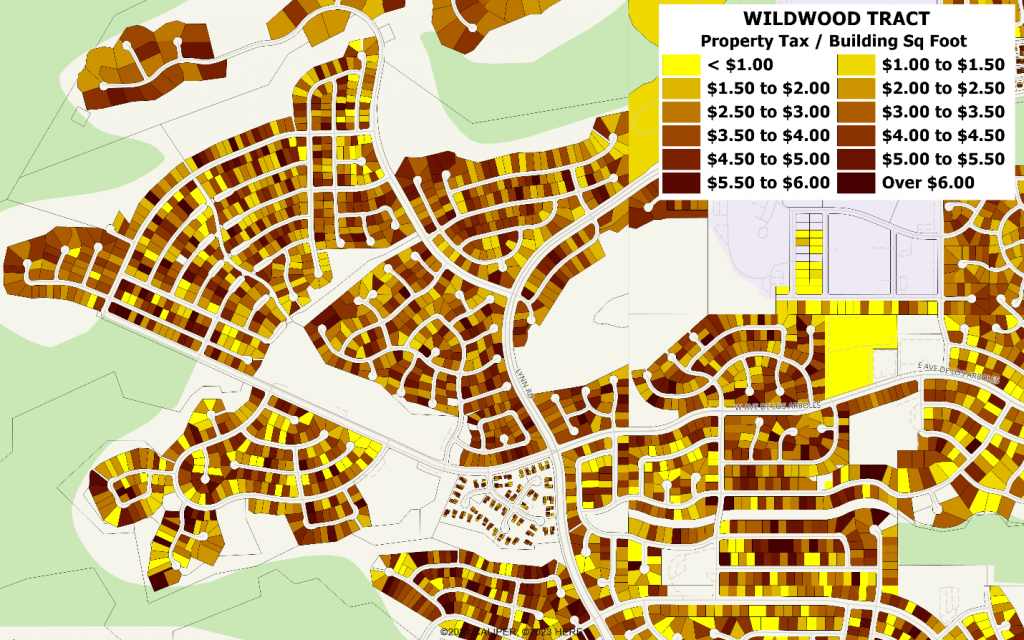

The Kevington and Conejo Oaks neighborhoods below were largely built in the 1960’s, and show an equal amount of variation in taxes per square footage of the dwelling:

A quick review shows the reason: the higher taxed properties have all changed ownership recently, while the very low taxed properties have typically been in the same hands since the mid-1990’s. Aside from the obvious inequity of the differential tax burden, solely because of when the house was bought, there are some other impacts:

- A sticky housing market. Homeowners are less likely to move the longer they own a house. Empty nesters often don’t downsize, because they would have triple the property taxes on a smaller home. The lack of downsizing results in higher prices for entry level homes, which ultimately adds to the housing deficit that has now existed for decades.

- Longer commutes and increased traffic volumes. A change in employment that takes your morning commute from 10 minutes to 90 minutes would normally get families thinking about moving. But if by moving, you quadruple your tax bill for an equivalent house, you are more likely to stay put and contribute to the legendary traffic.

It is inherently unfair that neighbors living in similar size and value houses pay considerably different amounts for what are effectively the same public services. Many would like Prop 13 to be reconsidered, but at this point, it is the third rail of California politics, and few candidates will even discuss it openly. Despite the current societal predilection for equity and equality, it is unlikely that this will be addressed anytime soon. The longer a resident has lived in a house, the more likely it is that they are retired and living on a fixed income, or likely to do so in the near future. Any changes to the system will almost by necessity need to be phased in over the course of a decade or longer.