Last week, the second named storm of the 2024 season – Beryl – made landfall with category 5 force, visiting Jamaica and Cancun, and eventually the south Texas coast before losing steam as it makes its way through the middle of the United States.

The chaos in a Barbados harbor on last Monday was well captured by Ricardo Mazalan (Associated Press):

Hurricane season, at least on the Atlantic coast, officially runs from June 1 to November 30 but generally peaks in September, when the difference in the air and surface ocean temperatures are greatest. The average hurricane season has 14 named storms, with half of them becoming hurricanes. In most years, 3 of them will become category 3 or higher at their peak intensity (Saffir-Simpson scale, winds over 110 miles per hour).

The NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) predicts that, because of a lingering La Nina and warmer than average ocean temperatures, we can expect between 17 and 25 named storms with perhaps 4 to 7 major hurricanes. Beryl is likely the first of several storms to menace the Gulf and Atlantic coasts this year.

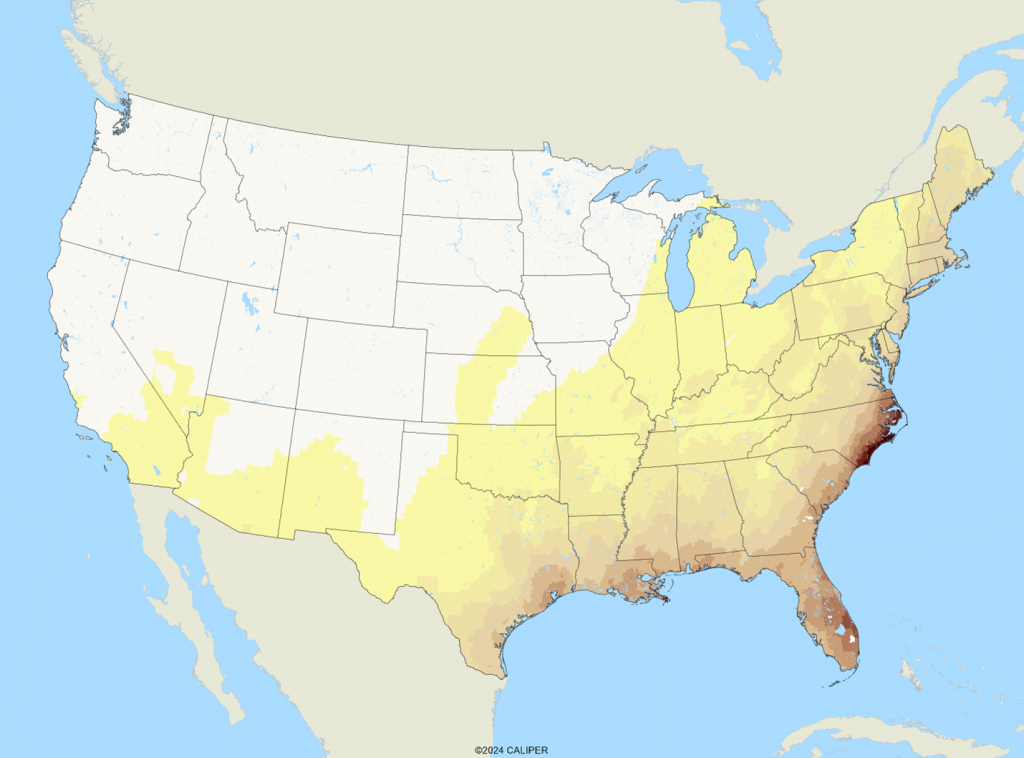

Historically, the highest risk area for hurricanes is between Cape Hatteras and Cape Fear on the North Carolina coast. Most of the damage from hurricanes is wind related – knocking trees and power lines down. Damage can occur quite far inland, and the risk profile for hurricanes extends far inland. The national hurricane risk map – including both Atlantic and Pacific storms – is below:

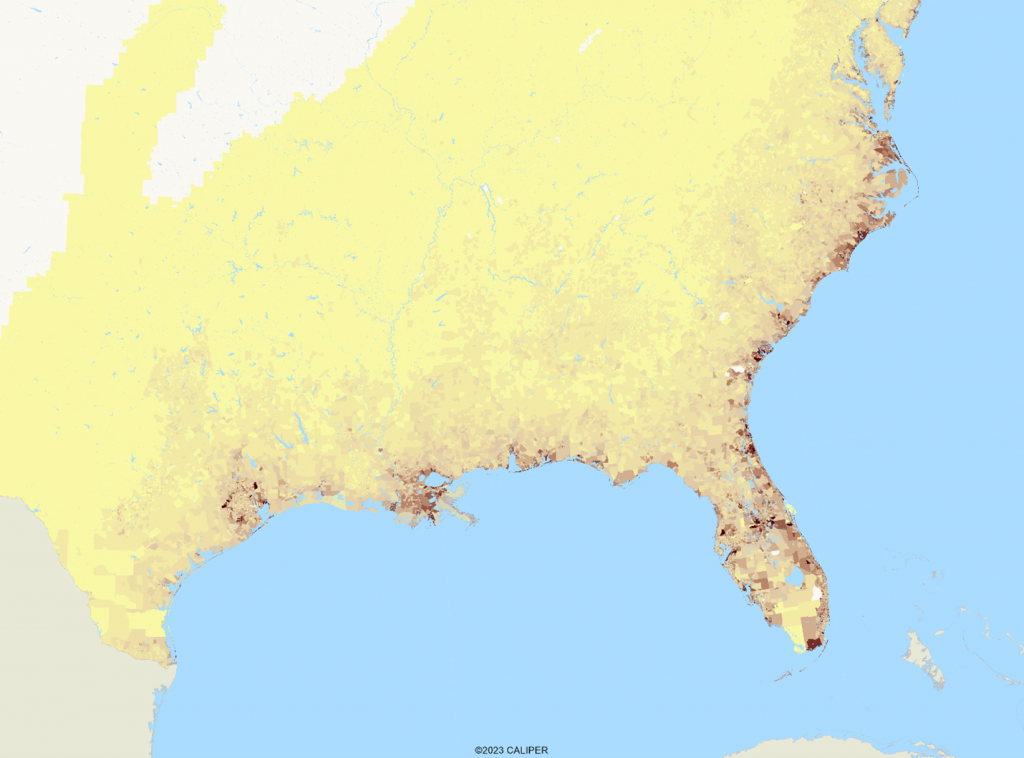

When we consider coastal storm surge risk, which is confined to low lying coastal areas, damage is confined to a narrow band along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, sometimes reaching several miles inland in the event of a major storm surge. The Katrina surge was recorded at about 25 feet, meaning all property below that elevation and exposed to the coastline was inundated:

Finally, we combined the two risk indexes and weighted the results by population in order to assess the relative potential for damage:

The expected hot spots for damage are the major cities, with significant inland damage possible in Central Florida. The fear is always that, like Katrina, a major hurricane will make landfall near one of the large coastal cities where damage can be extreme. Yet there are very few areas of the eastern coastlines which are not significantly exposed to risk, and in some areas such as the Florida peninsula, there are few places not at risk during this season. We always hope that people who live in these areas will make prudent preparations well in advance, even as we are accustomed to seeing the pictures of people stocking up on supplies hours ahead of landfall.

Recent Comments